Designing Circuits with VHDL

1. Introduction

VHDL is a hardware description language that can be used to

design digital logic circuits. VHDL specifications can be automatically

translated by circuit synthesizers into digital circuits, in

much the same way that Java or C++ programs are translated by compilers

into machine language. While VHDL code bears a superficial resemblance

to programs in conventional sequential programming languages, the

meaning of VHDL code differs in important ways from sequential

programs. Ultimately, the meaning of a VHDL specification is a

circuit, while the meaning of an ordinary

program is the sequential execution of the program statements. The

underlying notion of sequential execution is so pervasive in ordinary

programming that it is easy to take it for granted. In VHDL, on the

other hand, there is no built-in concept of sequential execution and

this can be the source of much misunderstanding when first learning the

language. Understanding the differences between circuit design in VHDL

and conventional programming is one of the key steps in learning to

use the language. Don't worry. You're not expected to understand these

differences yet, but you should be aware of them. As we go along,

you'll

recognize and start to appreciate the differences and their

implications.

2. Combinational Circuits

Signal Assignments in VHDL

Combinational circuits can be represented by

circuit schematics using logic gates. For example,

Equivalently, we can represent this circuit by the Boolean equation A

= BC + D´. VHDL

allows us to specify circuits with equations in much the same way.

A

<= (B and C) or (not D);

Here, A, B, C and D are names of VHDL signals; <= is the concurrent

signal assignment operator and the keywords and, or and not are the familiar

logical operators. The parentheses are used to determine the order of

operations (in this case, they are are not strictly necessary,

but do help make the meaning more clear) and the semicolon terminates

the assignment. A combinational circuit can have multiple outputs,

as in the full adder shown below.

We can represent this with a pair of Boolean equations or the

equivalent VHDL signal assignments.

S <=

A xor B xor Ci;

Co <= (A and B) or ((A xor B) and Ci);

In general, a logic circuit with n outputs can be represented

by n signal assignments. The signal

assignments are only part of a VHDL specification. Here is the complete

specification of the full adder.

library IEEE;

use IEEE.STD_LOGIC_1164.ALL;

use IEEE.STD_LOGIC_ARITH.ALL;

use IEEE.STD_LOGIC_UNSIGNED.ALL;

entity fullAdder is

port( A,B: in std_logic; -- input

bits for this stage

Ci: in std_logic; -- carry into this stage

S: out std_logic; -- sum bit

Co: out std_logic -- carry out of this stage

);

end

fullAdder;

architecture a1 of

fullAdder is

begin

S <= A xor B xor Ci;

Co <= (A and B) or ((A

xor B) and Ci);

end a1;

The first four lines specify a library of standard definitions. We'll

just treat this as a required part of the specification, without going

into details. The next group of seven lines is the entity

declaration for our full adder circuit. The entity declaration

defines the name of the circuit (fullAdder), its inputs

and outputs and their types (std_logic). The inputs

and outputs are specified in a port list. Successive elements

of the port list are separated by semicolons (note that there is

no semicolon following the last element). A pair of dashes introduces a

comment, which continues to the end of the line. Comments don't

affect the meaning of the specification, but are essential for making

it readable by other people. It's a good idea to use comments to

identify the inputs and outputs of your circuits, document what

your circuits do and how they work. Get in the habit of documenting all

your code. The last five lines above, constitute the architecture

specification, which includes our two signal assignments. VHDL

permits you to have multiple architectures for the same entity, hence

the architecture has its own label, separate from the entity name.

It's important to understand the distinction between the entity

declaration and the architecture. The entity declaration defines the

name of the circuit and the architecture defines its implementation. In

a block diagram or

"abridged" schematic, we often show a portion of a larger circuit as a

block with labeled inputs and outputs, as illustrated below for the fullAdder.

This corresponds directly to the entity declaration. When we supplement

such a diagram, by filling in the block with an appropriate schematic,

we are specifying an architecture.

In the fullAdder

specification, all the signals are either inputs or outputs. We can

also have internal signals, much as we have internal variables in

ordinary programming languages. For example, we could write the fullAdder architecture

this way.

architecture a1 of fullAdder is

signal X: std_logic;

begin

X <= A

xor B;

S <=

X xor Ci;

Co <= (A and B) or (X and Ci);

end a1;

The signal declaration is required and specifies the type of X. VHDL is a strongly

typed language and requires that signals have the proper types.

Signal declarations appear before the begin keyword of the

architecture. The diagram for this architecture shown below, also

includes the signal X

explicitly and the use of X in both of the output

signals. Note that the order of the signal assignments, in this case,

has no effect on the meaning of the specification. In particular, if we

put the assignment to X

last, the resulting circuit would be exactly the same. This may seem

strange, but it illustrates how VHDL is different from ordinary

programming. The signal assignments are Boolean equations specifying

logic circuits. The order in which

you write the equations does not affect the meaning of the circuit

any more than the way you draw the corresponding schematic diagram

affects how it works.

VHDL also lets us define and use vectors of signals.

architecture

a1 of vecExample is

signal a, b: std_logic_vector(0 to 7);

signal c: std_logic_vector(7 downto 0);

begin

b <= "10101010"; -- double

quotes used for arrays of bits

a <=

b and "00011111";

c <= a(4 to 7) & b(0 to 3);

end

a1;

The std_logic_vector

type can have indices that either increase or decrease in value as you

go from "left-to-right". The direction of the indices affects how

assignments involving vectors are interpreted, as we will see shortly.

For signals that are used to represent numerical values,

it's usual to have the indices decrease. A signal assignment involving

logic vectors can be thought of as just a short hand for a group of

signal assignments. For example, the first assignment above is

equivalent to

b(0)

<= '1'; b(1)

<= '0'; b(2)

<= '1'; b(3)

<= '0';

b(4)

<= '1'; b(5)

<= '0'; b(6)

<= '1'; b(7)

<= '0';

Here, the notation b(i)

refers to the individual elements of the vector. In the second

assignment, the and operator

is applied bit-wise, so the meaning of the assignment is

a(0) <= b(0) and '0'; a(1) <= b(1) and '0';

a(2) <=

b(2) and '0'; a(3) <= b(3) and '1';

a(4) <=

b(4) and '1'; a(5) <= b(5) and '1';

a(6) <=

b(6) and '1'; a(7) <= b(7) and '1';

The last assignment refers to sub-vectors of a and b and uses the concatenation

operator &.

Also note that the indices for c run in the opposite

order of the indices for a

and b, so the

meaning of this assignment is

c(7) <=

a(4); c(6) <= a(5); c(5) <= a(6); c(4) <= a(7);

c(3) <=

b(0); c(2) <= b(1); c(1) <= b(2); c(0) <= b(3);

In principal, we can define any combinational logic circuit using just

simple signal assignments. In more complex circuits it's convenient to

have higher level constructs. The conditional signal assignment

allows us to make the value assigned to a signal dependent on a series

of conditions.

entity

conditionalExample is

port(a, b, c: in std_logic; d: out std_logic);

end conditionalExample;

architecture a1 of conditionalExample is

begin

d <= '1' when a = b else

b

when b /= c else

a xor c;

end a1;

The comparison operators '='

and '/=' in

the when clauses are true if the two operands are equal or not

equal, respectively. The conditional signal assignment is not strictly

necessary, since the following ordinary assignment is equivalent.

d <= ((a xnor b) and '1')

or

(not (a xnor b) and (b

xor c) and b) or

(not (a xnor b) and

not (b xor c) and (a xor c));

While VHDL allows the comparison operators in the condition part

of the when clauses, they cannot be used

in ordinary assignments, but the xnor and xor operations can

serve the same purpose. Note the pattern of the transformation from the

conditional assignment to the ordinary assignment. Overall, the new

expression is the logical-or of several sub-expressions, one for each

part of

the conditional assignment. Each sub-expression is the logical-and

of the condition in one of the when clauses, the complement of the

conditions in the previous when clauses and the value associated with

the 'current' clause. Of course, we could also simplify this

expression, giving

d <=

not(a and (not b)

and c);

but it's certainly easier to let the synthesizer do the logic

simplification so that we can concentrate on the higher level meaning

of the circuit. The conditional assignment is one

tool for allowing us to express the circuit behavior at a somewhat

higher level. The general form of the conditional assignment is

x<= value1 when condition1 else

value2 when condition2 else

value3 when condition3 else

... else

valuen

Each of the values must have the same type as the signal

on the left side of the assignment. Each of the conditions is a Boolean

function on some set of variables. The equivalent form of ordinary

signal assignment is

x<= (condition1

and value1) or

(not condition1

and condition2

and value2) or

(not condition1

and not condition2

and condition3

and value3) or

...

(not condition1

and ... and not conditionn-1

and valuen)

We can also have conditional signal assignments involving logic

vectors. For example, if x,

a, b and c all have type std_logic_vector(3 down to 0)

and s has type std_logic_vector(1 downto 0),

we can write

x <=

a when s = "00"

else

a and b when s = "01"

else

a xor c when s = "10"

else

b;

As with ordinary signal assignments, we can view this as a short-hand

for four separate signal assignments operating on individual signals.

x(3)

<= a(3) when s(1) = '0'

and s(0) = '0' else

a(3) and b(3) when s(1) = '0'

and s(0) = '1' else

a(3) xor c(3) when s(1) = '1'

and s(0) = '0' else

b(3);

x(2)

<= a(2) when s(1) = '0'

and s(0) = '0' else

a(2) and b(2) when s(1) = '0'

and s(0) = '1' else

a(2) xor c(2) when s(1) = '1'

and s(0) = '0' else

b(2);

and so forth. Note that because the conditions in this case just

enumerate the different values of the signal s, the circuit

specified by the statement can be implemented with a 4:1 multiplexor

with a four bit wide data path.

Processes and Conditional Statements

VHDL provides a variety of higher level constructs that make it easier

to express more complex designs. In particular, it includes an if-then-else construct,

similar to those in ordinary programming languages. For example, we can

write

if a = '0' then

x

<= a; y <= b;

elsif a = b then

x

<= '0'; y <= '1';

else

x

<= not b; y <= not b;

end if;

VHDL requires that higher level constructs like the if-then-else be used

only inside a process block. So the complete architecture for a

module with inputs a, b and outputs x, y that includes the

above

logic would be

architecture a1 of

ifThenExample

is

begin

process(a,b)

begin

if a = '0' then

x

<= a; y <= b;

elsif a = b

then

x <= '0'; y <= '1';

else

x <= not b; y

<= not b;

end if;

end process

end a1;

Following the process

keyword is a

list of signal names, which is called the sensitivity list. The

sensitivity list should include all signals that can trigger changes to

signals that are assigned values within the process. If we're using the

process to define a combinational circuit, this means that the

sensitivity list should include all signals that appear in any

expression within the process. Note that we could have specified a

circuit with

the same behavior using two conditional assignment statements, one

for x and one for y. Or, we could have

written them using two ordinary signal assignments. For this simple

example, those alternatives might be preferable, but for more complex

circuits, the use of the if-then-else

construct can make it easier to express the logic you have in

mind and easier for others to read and understand your VHDL code.

There is an important rule that must be followed

when using a process to define a combinational circuit.

Every signal that is assigned a value inside a process

must be defined for all possible conditions.

The process above satisfies this condition, but the following version

does not.

architecture a1 of

ifThenExample

is

begin

process(a,b)

begin

if a = '0' then

x

<= a ; y <= b;

elsif a = b

then

x <= '0'; y

<= '1';

else

x <= not b;

-- y not defined when a=1, b=0

end if;

end process

end a1;

While this is a legitimate VHDL specification, it does not correspond

to any combinational circuit. The reason for this is that VHDL defines

the value of a signal to be unchanged by a process if its value is not

specified under some condition. So in this case, the value of y would not change when a=1 and b=0. To create

a circuit that has this behavior, the synthesizer must provide a

storage element (typically a latch) to retain the value of y in this case. The

circuit shown below has the specified behavior:

So if you are intending to implement a combinational circuit, it's

important to pay attention to this rule. If you

don't, the circuit synthesized for your specification will contain

storage elements that may cause it to behave differently than you

intended. It's easy to violate this rule and it can be hard to figure

out what's wrong when you do, so be aware of it and try to adopt coding

practices that will keep you from making such mistakes. One simple

way to avoid the problem is to always start your process with

assignments of default values for all signals that are assigned

a value

within the process. For example, we could write

architecture a1 of

ifThenExample

is

begin

process(a,b)

begin

x <= '0'; y

<= '0'; -- default values for x, y

if a = '0' then

x

<= a; y <= b;

elsif a = b

then

x <= '0'; y <= '1';

else

x <= not a; --

y=0 when a=1, b=0

end if;

end process

end a1;

Now, if you intended to write the original

version of this code, the above specification would still

be incorrect, but at least it specifies a combinational circuit and

you'll have an easier time figuring out what you did wrong than you

would if the circuit had a "hidden" storage element.

Note that for the above code to work as intended, the assignments of

the default values must come before the if-then-else. This is a

case where statement order matters. While the effect of statement order

is similar to that in ordinary programming languages, the

underlying reasons are a little different, since in VHDL, there

is no built-in concept of sequential execution. Whenever there

are two assignments to the same variable the later one takes precedence

in all conditions allowed by the context in which it appears. So

for example, in this architecture

architecture a1 of foo is

begin

process(a,b)

begin

c <= '0';

if a = b then

c

<= '1';

end if;

end process

end a1;

the first assignment to c

applies no matter what values a and b have, while the second

applies only when a=b.

Because the second assignment comes after the first one, it overrides

the first, when a=b.

If we wrote

architecture a1 of foo is

begin

process(a,b)

begin

if a = b then

c

<= '1';

end if;

c <= '0';

end process

end a1;

the resulting circuit would make c=0, not matter what

value a and b had. While the first

version is equivalent to

architecture a1 of foo is

begin

c <= a

xnor b;

end a1;

the second is equivalent to

architecture a1 of foo is

begin

c <= '0';

end

a1;

The implications of statement order within a VHDL process are a

little bit tricky. To explore this issue further, suppose we have the

following signal assignments in a VHDL specification within a process.

A <=

'1'; -- '1' denotes the constant logic value 1

B <= A;

A <= '0'; -- '0' denotes the constant

logic value 0

If these were assignments in a sequential language, the value assigned

to B would be 1. However, in

VHDL, B's

value is 0.

Why? The key to this is understanding how VHDL interprets the two

assignments to A.

The first assignment says that the signal A is wired to a constant

value of 1 in

the logic circuit defined by the code. The second says that A is wired a constant

value of 0.

They can't both be true, so how does VHDL interpret these two

contradictory statements? While it could just reject them as

a coding error, it does not. Instead, it simply ignores the first one

(in general, it ignores all but the last assignment to a given signal

in situations like this). So, the signal B is wired to the signal

A, which is wired

to

the constant 0,

meaning that B is

also

wired to 0.

Note

that if we reversed the order of the two assignments to A, the meaning of the

specification (that is the circuit defined by the specification) would

change. So, while the order of signal assignments to A does matter, the

position of the assignment to B does not.

Note that we would not normally write the code fragment above in VHDL,

since it doesn't really make sense in the VHDL context. Also, it's

important to recognize that this code fragment is treated differently

if it lies

outside a process block. In that case, the output A is treated as though

it

is simultaneously wired to both a logic 1 and a logic 0. A

simulator

will typically show the value of A as being undefined and

a synthesizer will typically reject the circuit as physically

meaningless. (Of course, if the synthesizer were to synthesize a real

physical circuit as specified, and you applied power to it, the result

would be a short

circuit between power and ground, creating a small puff of smoke, an

unpleasant smell and a useless lump of silicon.)

Case Statements

VHDL provides a case statement that is useful for specifying different

results based on the value of a single signal. For example,

architecture a1 of foo is

begin

process(c,d,e) begin

b <= '1';

-- provide

default value for b

case e is

when "00"

=> a <= c; b <= d;

when "01"

=> a <= d; b <= c;

when "10"

=> a <= c xor d;

when others => a

<= '0';

end case;

end process;

end a1;

Anything you can do with a case

statement, you can also do with an if-then-else construct,

but often the case is

more convenient. Also, in those circumstances where it is appropriate,

a circuit synthesizer will generally produce a more efficient circuit

for a

case than it will

for an if-then-else.

For Loops

VHDL provides a for-loop

which is similar to the looping constructs in sequential programming

languages. We can use it to define repetitive circuits, like the adder

shown below. In this example, we also introduce the use of constants to

define

the size of the words that the adder operates on. The constant is

declared

in the package named commonConstants and is

referenced

by a use clause

before

the entity declaration. Packages are used to collect commonly used

declarations

in one place so that they can be used in different parts of the design.

It's a good practice to use named constants in this way, to make the

code

easier to understand and to facilitate making changes.

package commonConstants is

constant wordSize: integer :=

16;

end package commonConstants;

library IEEE;

use IEEE.STD_LOGIC_1164.ALL;

use IEEE.STD_LOGIC_ARITH.ALL;

use IEEE.STD_LOGIC_UNSIGNED.ALL;

use work.commonConstants.all; -- makes package

visible to entity

entity

adder is

port(A, B: in

std_logic_vector(wordSize-1 downto 0);

Ci: in

std_logic;

S: out

std_logic_vector(wordSize-1 downto 0);

Co: out

std_logic

);

end adder;

architecture a1 of adder is

signal C: std_logic_vector(wordSize downto 0);

begin

process (A,B,C,Ci) begin

C(0) <= Ci;

for i in 0 to

wordSize-1 loop

S(i) <= A(i) xor B(i) xor C(i);

C(i+1) <= (A(i) and B(i)) or

((A(i)

xor B(i)) and C(i));

end loop;

Co <=

C(wordSize);

end process;

end a1;

The for-loop is equivalent to wordSize pairs of

assignments and while we could define the circuit that way, the loop is

certainly much more convenient and easier to understand. You might

wonder why we used a logic vector for the signal C. Wouldn't it be

simpler to write

architecture a1 of adder is

signal C: std_logic;

begin

process (A,B,C,Ci) begin

C <= Ci;

for i in 0

to wordSize-1 loop

S(i) <= A(i) xor B(i) xor C;

C <=

(A(i) and B(i)) or

((A(i)

xor B(i)) and C);

end loop;

Co <= C;

end process;

end a1;

While this makes perfect sense in a sequential programming languages it

does not have the intended meaning in VHDL, since there is no built-in

concept of sequential execution. The signal C can only be "wired"

one

way. It cannot be defined by different expressions at different times.

Consequently, the circuit defined by this specification will not behave

in the intended way.

Structural VHDL

Larger circuits are generally implemented by combining large building

blocks together using what is known as structural VHDL. In

structural VHDL, we essentially "wire" together the different

components to form a larger circuit. We can illustrate this by

constructing a 4 bit adder using the full adder module defined earlier

as a building block.

entity

adder4 is

port(A, B:

in std_logic_vector(3 downto 0);

Ci: in

std_logic;

S: out

std_logic_vector(3 downto 0);

Co: out

std_logic

);

end adder4;

architecture a1 of adder4 is

-- local

component declaration for fullAdder

component fullAdder port(

A, B, Ci: in std_logic;

S, Co: out std_logic

);

end

component;

signal

C: std_logic_vector(3 downto 1);

begin

b0: fullAdder port map(A(0),B(0),Ci,S(0),C(1));

b1: fullAdder port

map(A(1),B(1),C(1),S(1),C(2));

b2: fullAdder port

map(A(2),B(2),C(2),S(2),C(3));

b3: fullAdder port map(A(3),B(3),C(3),S(3),Co);

end a1;

The meaning of this specification is illustrated in the block diagram

shown below.

Note that structural VHDL does not use a process construct. To use a

component within a VHDL architecture, you must include a local

component declaration as part of the architecture. The component

declaration defines the interface to the architecture and is similar to

the entity declaration. The component declaration is required even if

the entity declaration for the component is in the same file. This is

because VHDL requires that each architecture be self contained. The

four component instantiation statements specify the four

full adders. Each statement has a label that is used to distinguish the

components from one another. The port map portion of the

component instantiation statement defines which signals of the adder4 module are

associated with which ports of the fullAdder component. In

this case, we are using positional association of the ports.

That is, the position of a signal in the port map list determines which

signal in the component declaration it is associated with. VHDL also

allows

named association. For example, we could write

b0: fullAdder port

map(A=>A(0),B=>B(0),S=>S(0),

Ci=>Ci,C0=>C(1));

Note that if we use named association, the order in which the arguments

appear does not matter. For larger circuit

blocks with many inputs and outputs, named association is preferred.

Structural VHDL also supports iterative definitions so that we need not

write a whole series of similar component instantiation statements.

This allows us to write the four bit adder as

architecture a1 of adder4 is

-- local component declaration for fullAdder

component fullAdder port(

A, B, Ci: in std_logic;

S, Co: out std_logic

);

end

component;

signal

C: std_logic_vector(4 downto 0);

begin

C(0) <= Ci;

bg: for i

in 0 to 3 generate

b: fulladder

port map(A(i),B(i),C(i),S(i),C(i+1));

end generate;

Co <= C(4);

end a1;

Observe that in this version, we've declared C to be a five bit

signal, rather than a three bit signal and associated Ci with C(0) and Co with C(4). This avoids the

need for separate component instantiation statements for the first and

last

bits of the adder. The for-generate

statement also allows us to define the adder using a named constant for

the word size, instead of explicit values. This makes the code more

general and easier to change, if we decide that we need a different

word size. Note that the labels on the for-generate statement

and on the component instantiation statement are both required. Finally

we should point out that while we can use structural VHDL to define

circuits like the adder, usually it is more convenient to define

circuits like this with for-loops,

as discussed earlier. Structural VHDL is most useful for putting

together larger circuit blocks.

3. Sequential Circuits

What distinguishes sequential circuits from combinational circuits is

the fact that they can store values and retain them for later use.

Clocked sequential circuits store values in flip flops, most often,

edge-triggered D flip flops. VHDL provides a syncronization

condition for use in if-statements

that allows us to specify the storage of values in flip flops or

registers of flip flops. Here's an example.

if

rising_edge(clk) then

x <= a xor b;

end if;

The expression in the if-statement

is the syncronization condition. Here clk, is a clock signal.

The event

attribute is true whenever clk is changing. The

second part of the synchronization condition refers to the value of clk immediately after

the transition. So this synchronization condition says that the signal x should be assigned the

value a xor b on a

rising clock edge. To implement this behavior the circuit synthesizer

associates the signal x

with the output of a positive edge-triggered D flip flop. Note that

because x is the

output of a flip flop, it can only change when the flip flop changes.

This means

that all assignments to x

must be within the scope of if-statements with

identical synchronization condition. This requirement makes it

convenient to arrange one's VHDL specification so that all assignments

to signals whose values are stored in flip flops lie within the scope

of a single if-statement

containing the synchronization condition. In fact, while the language

doesn't require this, many circuit synthesizers cannot handle

specifications with more than one synchronization condition in the same

process. For this reason, we adopt the common convention of using at

most one synchronization condition in the processes used to specify

sequential circuits.

VHDL makes it easy to write a specification for a sequential circuit

directly from the state transition diagram for the circuit. The state

diagram shown below is for a sequential comparator with

two serial inputs, A

and B and two

outputs

G and L. There is also a reset input that

disables

the circuit and causes it to go the 00 state when it is high. After

reset

drops, the A and B inputs are

interpreted

as numerical values, with successive bits presented on successive clock

ticks, starting with the most significant bits. The G and L outputs are low

initially, but as soon as a difference is detected between the two

inputs,

one or the other of G

or L goes

high. Specifically, G

goes high if A>B

and L goes

high

if A<B. Notice

that

G and L go high before the

clock tick that causes the transition to the 10 and 01 states.

Here is a VHDL module that implements the comparator.

entity serialCompare is

Port (clk, reset: in std_logic;

A, B : in std_logic; -- inputs to be compared

G, L: out std_logic -- G means A>B,

L means A<B

);

end serialCompare;

architecture a1 of serialCompare is

signal state: std_logic_vector(0 to 1);

begin

-- process that defines state

transition

process(clk)

begin

if rising_edge(clk) then

if reset = '1' then

state <= "00";

elsif state = "00" then

if A = '1' and B = '0' then

state <= "10";

elsif A = '0' and B = '1' then

state <= "01";

end if;

end if;

end if;

end process;

-- process that defines the outputs

process(A, B, state) begin

G <= '0'; L <= '0';

if (state = "00"

and A = '1' and B = '0')

or state = "10" then

G <= '1';

end if;

if (state = "00"

and A = '0' and B = '1')

or state = "01" then

L <= '1';

end if;

end process;

end a1;

There are two processes in this specification. The first

defines the state transitions and starts with an if-statement containing

a synchronization condition. All assignments to the state signal occur

within

the scope of this if-statement

causing them to be synchronized to the rising edge of the clk signal. We start the

synchronized code segment by checking the status of reset and putting the

circuit into state 00 if reset is high, The

rest of the process controls the transition to the 10 or 01 states,

depending on which of the two inputs is larger. Notice that there is

no code for the "self-loops" in the transition diagram, since these

involve

no change to the state signal. The second process specifies the output

signals G and L. Although it's not

essential to define the outputs in a separate process, it's generally

considered

good practice to do so. Notice that this second process has no

synchronization condition and specifies a purely combinational

sub-circuit. The VHDL synthesizer analyzes this specification and

determines that the state

signal must be stored in a pair of flip flops. It also determines the

logic equations needed to generate the next state and output values and

uses these to create the required circuit. The diagram below shows a

circuit that could

be generated by the synthesizer from this specification.

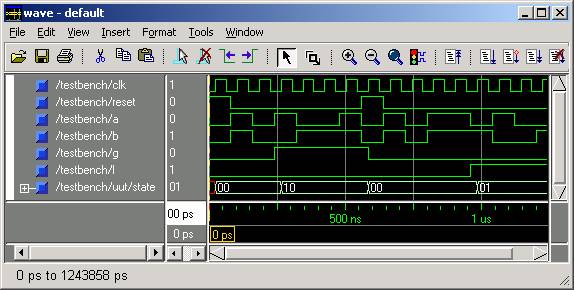

The figure below shows the output of a simulation run for the serial

comparator. Notice that the changes to the state variable are

synchronized to the rising clock edges but the the low-to-high

transitions of G

and L are not.

VHDL allows us to define signals with enumerated types allowing

us to associate meaningful names to values of signals. This is

particularly useful for naming the states of state machines, as

illustrated below.

architecture a1 of

serialCompare is

type stateType is (unknown, bigger, smaller);

signal state: stateType;

begin

-- process that defines state

transition

process(clk)

begin

if rising_edge(clk) then

if reset = '1' then

state <= unknown;

elsif state = unknown then

if A = '1' and B = '0' then

state <= bigger;

elsif A = '0' and B = '1' then

state <= smaller;

end if;

end if;

end if;

end process;

-- code that defines the outputs

G <= '1' when (state = unknown and A = '1' and B= '0')

or state = bigger else

'0';

L <= '1' when (state = unknown and A = '0' and B= '1')

or state = smaller else

'0';

end a1;

In this version, we have also defined the outputs with two conditional

signal assignments, instead of a process. In situations where the

outputs are fairly simple, this coding style is preferable.

Next, we look at an example of a more complex sequential circuit that

combines a small control state machine with a register to count the

number of "pulses" observed in a serial input bit stream, where a pulse

is defined as one or more clock ticks when the input is low, followed

by one or more clock ticks when it is high, followed by one or more

clock ticks when it is low. In addition to the data input A, the circuit has a reset input, which

disables and re-initializes the circuit. The primary output of the

circuit is the value of the four bit counter. There is also an error output which is

high if the input bit stream contains more than 15 pulses. If the

number of pulses observed exceeds 15, the counter "sticks" at 15. The

simplified state transition diagram shown below does not explicitly

include the

reset logic, which clears the counter and puts the circuit in the allOnes state. Also,

note

that the counter value us not shown explicitly, since this would

require

that the diagram include separate between and inPulse states for each

of the distinct counter values. Instead, we simply show whether the

counter is incremented or not.

Here is a VHDL module that implements pulse counter. In this example,

we have introduced two constants, one for the word size and another for

the maximum number of pulses that we can count. Note that because the

second constant has type

std_logic_vector, the package declaration requires the IEEE

library where the std_logic_vector

type is defined. Notice the correspondence between the transition

diagram and the code.

library

IEEE;

use IEEE.STD_LOGIC_1164.ALL;

package commonConstants is

constant wordSize: integer :=

4;

constant maxPulse:

std_logic_vector := "1111";

end package commonConstants;

library IEEE;

use IEEE.STD_LOGIC_1164.ALL;

use IEEE.STD_LOGIC_ARITH.ALL;

use IEEE.STD_LOGIC_UNSIGNED.ALL;

use work.commonConstants.all;

-- Count the number of pulses in the input bit

stream.

-- A pulse is a 01...10 pattern.

entity countPulse is

Port (

clk,

reset: in std_logic;

A: in std_logic; -- input bit

stream

count: out

std_logic_vector(wordSize-1 downto 0);

errFlag: out

std_logic -- high if more than maxPulse detected

);

end countPulse;

architecture a1 of countPulse is

type stateType is (allOnes, between, inPulse,

errState);

signal state: stateType;

signal countReg: std_logic_vector(wordSize-1 downto

0);

begin

process(clk) begin

if rising_edge(clk) then

if reset = '1' then

countReg <= (others => '0');

state <= allOnes;

else

case state is

when allOnes =>

if A = '0'

then state <= between; end if;

when between =>

if A = '1'

then state <= inPulse; end if;

when inPulse =>

if A = '0' and

countReg /= maxPulse then

countReg <= countReg + "1";

state <= between;

elsif A = '0'

and countReg = maxPulse then

state <= errState;

end if;

when others =>

end case;

end if;

end if;

end process;

count <= countReg;

errFlag <= '1' when state =

errState else '0';

end a1;

Notice that we have defined a countReg signal separate

from the count

output signal because VHDL does not allow output signals to be used in

expressions. The standard way to get around this is to have an internal

signal that is manipulated within the module and then assign the value

of this internal signal to the output signal. Also notice the

assignment to countReg

in the reset section.

countReg <= (others => '0');

This means that all bits of the countReg are 0. We could have written

countReg <= "0000";

but this makes the code dependent on the word size, which we would

prefer to avoid.

The countPulse

circuit illustrates a common characteristic of many sequential

circuits. While strictly speaking, the state of the circuit consists of

both the state

signal and the value of countReg,

the two serve somewhat different purposes. The state signal keeps tack

of the control state of the circuit while the countReg variable holds

the data state. We can generally simplify the state transition

diagram for a sequential circuit by representing only the

control state explicitly while indicating the modifications to the data

state as though they were outputs to the circuit. This leads directly

to a VHDL representation based directly on the transition diagram.

We finish this section with a larger sequential circuit that implements

a hardware priority queue. A priority queue

maintains a set of (key,value) pairs. Its primary output

is called smallValue

and it is equal to the value of the pair that has the smallest key.

So for example, if the priority queue contained the pairs (2,7), (1,5)

and (4,2) then the smallValue

output would be 5. There are two operations that can be performed on

the priority queue. An insert operation adds a new (key,value)

pair to the set of stored pairs. A delete operation removes the (key,value)

pair with the smallest key from the set. The circuit has the following

inputs.

clk the clock signal

reset initializes the

circuit, discarding any stored values that may be present

insert when high, it initiates an insert operation

delete when high, it initiates a delete operation;

however, if insert and delete are

high at the same time,

then the delete signal is ignored

key the key part of a new pair being

inserted

value the value part of a new pair being

inserted

The circuit has the following outputs, in addition to smallValue.

busy

is high when the circuit is in the middle of performing an

operation;

while busy is high, the insert and delete inputs are ignored; the

outputs are not required to have the correct values when busy is high

empty

is high when there are no pairs stored in the priority queue; delete

operations are ignored in this case

full

is high when there is no room for any additional pairs to be

stored;

insert operations are ignored in this case

The figure below shows a block diagram for one implementation of a

priority queue.

In this design, there is a set of blocks arranged in two rows. Each

block contains two registers, one storing a key, the other storing a

value. In addition, there is a flip flop called dp, which stands for

data

present. This bit is set for every block that contains a valid (key,value)

pair. The circuit maintains the set of stored pairs so that three

properties are maintained.

- For adjacent pairs in the bottom row, the pair to the

left has a key that is less than or equal to that of the pair on the

right.

- For pairs that are in the same column, the key of the

pair in the bottom row is less than or equal to that of the pair in

the top row.

- In both rows, the empty blocks (those with dp=0) are to the right

and either both rows have the same number of empty blocks or the top

row has one more than the bottom row.

When these properties hold, the pair with the smallest key is in the

leftmost block of the bottom row. Using this organization, it is

straightforward to implement the insert and delete operations. To

do an insert, the (key,value) pairs in the top row are

all shifted to the right one position, allowing the new pair to be

inserted in the leftmost block of the top row. Then, within each

column, the keys of the pairs in those columns are compared, and if

necessary, the pairs are swapped to maintain properties 2 and 3. Note

that the entire operation takes two steps. While it is in progress, the

busy output is high. The

delete operation is similar. First, the pairs in the bottom row are all

shifted to the left, effectively deleting the pair with the smallest

key.

Then, for each column, the key values are compared and if necessary,

the

pairs are swapped to maintain properties 2 and 3. Given these

properties, we can determine if the priority queue is full by checking

the rightmost dp

bit in the top row and we can determine if it is empty by checking the

leftmost dp

bit in the bottom row.

The complete state of this circuit includes all the values stored in

all the registers, but we can express the control state is much more

simply, as shown in the transition diagram below.

This is a somewhat conceptual state transition diagram, but it captures

the essential behavior we want. In particular, the labels on the arrows

indicate the condition that causes the given transition to

take place and any action that should be performed at the same

time.

The variable top(rightmost).dp refers to the

rightmost data present flip flop in the top row and bot(leftmost).dp

refers to the leftmost data present flip flop in the bottom row. In the

ready state, the circuit is between operations and waiting for

the next operation. If it gets an insert request and it is not full, it

goes to the inserting state and shifts the new (key,value)

pair into the top row and shifts the whole row right. From there it

makes a transition back to the ready state while doing a

"compare

& swap" between all vertical pairs. If the circuit gets a delete

request when it is in the ready state and is not empty, it goes

to the deleting state and shifts the bottom row to the left.

From

there, it immediately returns to the ready state, whild

performaning

a compare & swap.

A VHDL module implementing this design is shown below.

--

Priority Queue module implements a priority queue storing

-- up to 8 (key,value) pairs. The keys

and values are 4 bits

-- each. When the priority queue is not

empty, the output

-- smallValue is the value of a pair with the

smallest key.

-- The empty and full outputs report the status of the

priority

-- queue. The busy output remains high while an insert or

-- delete operation is in progress. While it is high, new

-- operation requests are ignored

entity

priQueue is

Port

(clk, reset : in std_logic;

insert, delete : in std_logic;

key, value : in

std_logic_vector(wordSize-1 downto 0);

smallValue : out std_logic_vector(wordSize-1 downto 0);

busy, empty, full : out std_logic

);

end priQueue;

architecture a1 of

priQueue is

constant rowSize:

integer := 4; -- local constant declaration

type pqElement is record

dp:

std_logic;

key:

std_logic_vector(wordSize-1 downto 0);

value: std_logic_vector(wordSize-1 downto 0);

end record pqElement;

type rowTyp is array(0

to rowSize-1) of pqElement;

signal top, bot: rowTyp;

type state_type is

(ready, inserting, deleting);

signal state: state_type;

begin

process(clk) begin

if rising_edge(clk) then

if reset = '1' then

for i in 0 to

rowSize-1 loop

top(i).dp <= '0'; bot(i).dp <= '0';

end loop;

state <=

ready;

elsif state = ready and insert =

'1' then

if

top(rowSize-1).dp /= '1' then

for i in 1 to rowSize-1 loop

top(i) <= top(i-1);

end loop;

top(0) <= ('1',key,value);

state <= inserting;

end if;

elsif state = ready and delete =

'1' then

if bot(0).dp

/= '0' then

for i in 0 to rowSize-2 loop

bot(i) <= bot(i+1);

end loop;

bot(rowSize-1).dp <= '0';

state <= deleting;

end if;

elsif state = inserting or state

= deleting then

for i in 0 to

rowSize-1 loop

if top(i).dp = '1' and

(top(i).key < bot(i).key

or

bot(i).dp = '0') then

bot(i) <= top(i); top(i) <=

bot(i);

end if;

end loop;

state <=

ready;

end if;

end if;

end

process;

smallValue <= bot(0).value when bot(0).dp = '1' else

(others => '0');

empty

<= not bot(0).dp;

full

<= top(rowSize-1).dp;

busy

<= '1' when state /= ready else '0';

end a1;

This example illustrates the use of arrays of records to represent the

two rows in the priority queue. The code segment

type

pqElement is record

dp: std_logic;

key: std_logic_vector(wordSize-1

downto 0);

value:

std_logic_vector(wordSize-1 downto 0);

end record pqElement;

defines the basic building block of the arrays. We can refer to

elements of the arrays or specific fields of specific elements using

expressions like

top(i) bot(i).value

Note how the use of the use of these arrays allows us to express the

design of the circuit in a way that directly reflects the high level

description.

Sequential circuits can be used to build systems of great

sophistication and complexity. The challenge, to the designer is to

manage that complexity so as not to be overwhelmed by it. VHDL is one

important tool that can help in meeting the challenge, but to use it

effectively, you need to learn the common patterns that experience has

shown are most useful in expressing the functionality of digitial

systems. This section has introduced some of the more useful patterns.

You should study the examples carefully to make

sure you understand how they work and to develop a familiarity with the

patterns they follow.

4. Functions and Procedures

Like conventional programming languages, VHDL provides a subroutine

mechanism to allow you to encapusulate circuit components that are used

repeatedly in different contexts. The example below shows how a

function can be used to represent a circuit that finds the first 1 in a

logic

vector.

entity

firstOne is

Port (a: in std_logic_vector(0 to wordSize-1);

x:

out std_logic_vector (0 to wordSize-1)

);

end firstOne;

architecture a1 of frstOne is

function firstOne(x: std_logic_vector(0 to wordSize-1))

return std_logic_vector

is

-- Returns a bit vector with a 1 in the position

where

-- the first one in the input bit string is found

-- everywhere else, it is zero

variable allZero: std_logic_vector(0 to wordSize-1);

variable fOne: std_logic_vector(0 to wordSize-1);

begin

allZero(0) := not x(0);

fOne(0) := x(0);

for i in 1 to wordSize-1 loop

allZero(i) := (not

x(i)) and allZero(i-1);

fOne(i) :=

x(i) and allZero(i-1);

end loop;

return fOne;

end function firstOne;

begin

x <= firstOne(a);

end a1;

Note that within the function definition, we can use the for-loop and other

complex statements. Also, note that within the function we use

variables not signals. When the function is invoked, the variables will

be associated with signals in the context from which the function is

invoked, but within the function definition, we use variables. When

assigning a value to a

variable, we must use the variable assignment operator :=.

We can use procedures to specify common subcircuits that produce more

than one output. In the example shown below, the firstOne function has

been modified so that it returns the numerical index of the first 1 in

the argument bit string, instead of a bit vector that marks the

position of the first 1. It is implemented using a separate encode procedure which

has two output parameters, one for the index, and the other for an

error flag. The firstOne

function inserts the error flag into the high order bit of its return

value.

package

commonConstants is

constant lgWordSize: integer := 4;

constant wordSize: integer := 2**lgWordSize;

end package

commonConstants;

library IEEE;

use

IEEE.STD_LOGIC_1164.ALL;

use

IEEE.STD_LOGIC_ARITH.ALL;

use

IEEE.STD_LOGIC_UNSIGNED.ALL;

use

work.commonConstants.all;

entity firstOne is

Port

(a: in std_logic_vector(0 to wordSize-1);

x: out std_logic_vector (lgWordSize

downto 0)

);

end firstOne;

architecture a1 of

firstOne is

procedure encode(x: in

std_logic_vector(0 to wordSize-1);

indx: out std_logic_vector(lgWordSize-1 downto 0);

errFlag: out std_logic) is

-- Unary to binary

encoder.

-- Input x is assumed to

have at most a single 1 bit.

-- Indx is equal to the

index of the bit that is set.

-- If no bits are set,

errFlag bit is made high.

-- This is conceptually

simple.

--

--

indx(0) is OR of x(1),x(3),x(5), ...

--

indx(1) is OR of x(2),x(3), x(6),x(7), x(10),x(11),

...

--

indx(2) is OR of x(4),x(5),x(6),x(7),

x(12),x(13),x(14(,x(15),...

--

-- but it's tricky to

code so it works for different word sizes.

type vec is array(0 to

lgWordSize-1) of std_logic_vector(0 to (wordSize/2)-1);

variable fOne: vec;

variable anyOne:

std_logic_vector(0 to wordSize-1);

begin

--

fOne(0)(j) is OR of first j bits in x1,x3,x5,...

--

fOne(1)(j) is OR of first j bits in x2,x3, x6,x7, x10,x11,...

--

fOne(2)(j) is OR of first j bits in x4,x5,x6,x7, x12,x13,x14,x15,...

for i

in 0 to lgWordSize-1 loop

for j in 0 to (wordSize/(2**(i+1)))-1

loop

for h in 0 to (2**i)-1 loop

if j = 0 and h

= 0 then

fOne(i)(0) := x(2**i);

else

fOne(i)((2**i)*j+h) := fOne(i)((2**i)*j+h-1) or

x(((2**i)*(2*j+1))+h);

end if;

end loop;

end loop;

indx(i) := fOne(i)((wordSize/2)-1);

end

loop;

anyOne(0) := x(0);

for i

in 1 to wordSize-1 loop

anyOne(i) := anyOne(i-1) or x(i);

end

loop;

errFlag := not anyOne(wordSize-1);

end procedure encode;

function firstOne(x:

std_logic_vector(0 to wordSize-1))

return std_logic_vector is

-- Returns the index of

the first 1 in bit string x.

-- If there are no 1's

in x, the value returned has a

-- 1 in the high order

bit.

variable allZero:

std_logic_vector(0 to wordSize-1);

variable fOne:

std_logic_vector(0 to wordSize-1);

variable rslt:

std_logic_vector(lgWordSize downto 0);

begin

allZero(0) := not x(0);

fOne(0) := x(0);

for i

in 1 to wordSize-1 loop

allZero(i) := (not x(i)) and allZero(i-1);

fOne(i) := x(i) and allZero(i-1);

end

loop;

encode(fOne,rslt(lgWordSize-1 downto 0),rslt(lgWordSize));

return rslt;

end function firstOne;

begin

x

<= firstOne(a);

end a1;

Functions and procedures can be important components of a larger VHDL

circuit design. They eliminate much of the repetition that can occur in

larger designs, facilitate re-use of design elements developed by

others and can make large designs easier to understand and manage.

5. Closing Remarks

This tutorial is just an introduction to VHDL and makes no attempt to

be comprehensive. VHDL is a large, complex language with a great many

features that while useful in some contexts, are not essential to the

development of smaller digital systems. There are a great many books

describing VHDL that you'll find useful as you progress through later

courses and apply VHDL to more complex systems. As you learn more about

the language, you will

discover that using VHDL to synthesize circuits is only one of its

uses.

In fact, the original purpose of the language was to model digital

systems

in software, to enable rapid simulation and evaluation of architectural

alternatives before proceeding with a specific design. The development

of

circuit synthesizers that could convert VHDL specifications into actual

hardware descriptions came later, only after the language was in

wide-spread use for modelling and simulation. As a result of this

history, it's possible to write VHDL specifications that, while they

can be simulated, cannot be synthesized. In this tutorial, we have

emphasized synthesizable VHDL specifications, and indeed, all the

examples in this tutorial can be (and have been) synthesized.

Last updated 1/2/05.