Efficient heap implementations are usually built around the idea of a

heap-ordered tree,

which is a tree in which each heap item $i$ is viewed as a tree node and

$\key(i) \geq \key(p(i))$ where

$p(i)$ is the parent of $i$ in the tree.

This property ensures that the root of the tree has the

smallest key value.

Using a suitably structured heap-ordered tree, the various operations

can be implemented to run in $O(\log n)$ time.

Array Heap

The array heap (also known as a $d$-heap) is a simple version

of the heap data type that uses an array to implement a

$d$-ary heap-ordered tree.

The provided Javascript implementation

includes the following methods in addition to the

three standard ones mentioned earlier.

The property $d$ is the “arity” of the heap-ordered tree. The size property is the number of items in the heap. The web app can be used to construct a heap from a string and try out its methods as shown below.

let h = new ArrayHeap(10);

h.fromString('{e:1 f:2 c:5 a:5 d:2 h:7 i:7 j:8 b:6 g:4}');

log(h.toString(1));

let u = h.deletemin();

log(h.x2s(u), h.key(u), ''+h);

This produces the output

{e:1(f:2(a:5(j:8 b:6) d:2(g:4)) c:5(h:7 i:7))}

e 1 {f:2 d:2 a:5 j:8 b:6 g:4 c:5 h:7 i:7}

The first line shows a detailed view of the heap,

before the $\deletemin$ operation.

Parentheses are used to indicate the tree structure.

Specifically, each item with children in the tree is

immediately followed by a parenthesized list of its children.

So for example, $a$ and $d$ are the two children of $f$.

The final line includes a more concise view of the heap,

just listing all the remaining items and their keys, in some unspecified order.

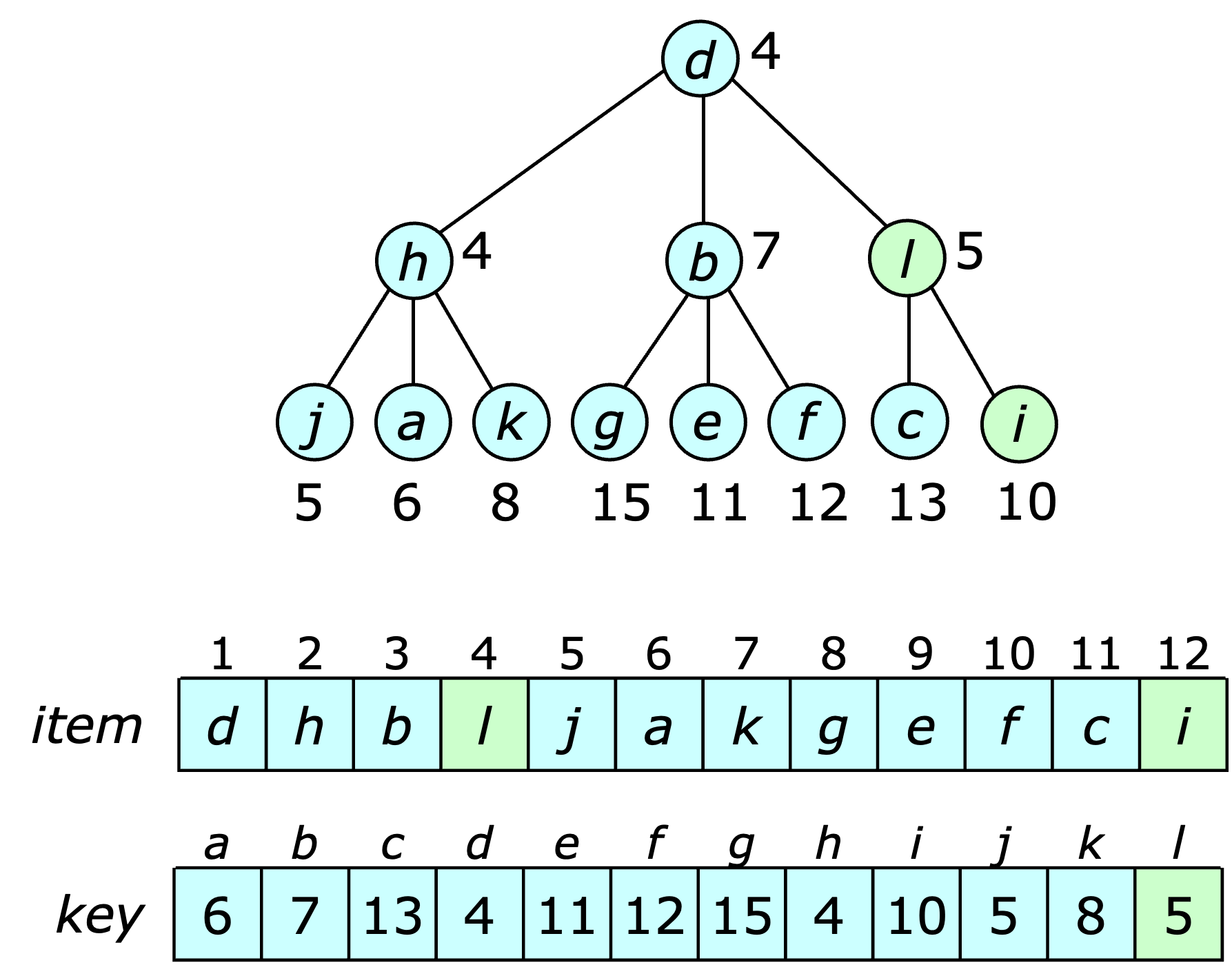

The implementation of the array heap stores the $m$ heap items in positions $1\ldots m$ of an array with the positions of items determining the relationship between parents and children in an implicit heap-ordered tree. This tree has a characteristic heap-shape, which is illustrated in the example below.

The index of an item in the item array is referred to as its position in the heap, so in the example, item $b$ is at position 3. The index of a value in the key array is an item number. Here, they are shown as letters to make it easier to distinguish the items from the other numeric values. For a heap item $i$ stored at position $x>1$, the parent of $i$ is stored at position $\lceil (x-1)/d \rceil$. Consequently, the children of $i$ (if any) are stored starting at position $d(x-1)+2$ and continuing consecutively from there. If $i$ has $d$ children its “rightmost” is stored at position $dx+1$. A third array $pos$ is included to support operations on arbitrary heap items (such as $\delete$); $pos[i]$ gives the position of item $i$ in the item array.

To insert a new item $u$ into a heap with key $k$, start at the first unused position in the item array, then go up the tree looking for the first item with a key that is $\leq k$. The new item becomes a child of that item and the other items along the path all move down one level in the tree. So for example, inserting item $l$ with key 5 into the previous example heap yields the following.

The insertion is done with the assistance of a helper method $\siftup(i, x)$, which scans for a position for item $i$ starting from position $x$, moving items down as it goes, before inserting $i$ into its final position.

The $\deletemin$ operation is implemented in a similar way. Let $i$ be the last item in the item array and let $k = \key(i)$. Starting from the root, scan down the heap looking for a new place to insert $i$. At each step, select the child of the current item that has the smallest key. When this process reaches an item with a key that is at least as large as $k$, item $i$ is inserted just above that item, while the other items in the search path are moved up one level. So for example, a $\deletemin$ on the heap from the last example, yields the configuration shown below.

The search process described above is implemented by a helper method called $\siftdown$.

The $\addtokeys$ method is implemented by adding an increment to an internal offset The key of an item is equal to the sum of the stored key value and the offset. When an item is inserted into the heap, the key value stored must adjusted to match the offset.

The core methods for the $\ArrayHeap$ class are shown below.

The running time for siftup is $O(\log_d n)$, while

the running time for siftdown is $O(d \log_d n)$.

The changekey operation can also be implemented using

siftup to reduce the key value and siftdown to increase

the key value. Hence, its running time is either $O(\log_d n)$

or $O(d \log_d n)$, depending on whether the key is increased or

decreased.

In some applications key reductions may occur more frequently than

other operations. In such cases, the overall performance can be

improved by selecting a value of $d$ that makes these operations faster

at the expense of the others.

Fibonacci Heaps

The $\FibHeaps$ [FreTar87] data structure represents a collection

of heaps that define a partition over a common index range $1\ldots n$.

Each heap is identified by one of its items.

The data structure supports an efficient meld operation which

combines two heaps into a single heap.

It can also implement a changekey operation that takes

essentially constant time when the key value is reduced;

operations that increase the key value take $O(\log n)$ time.

More precisely, in a sequence of $m$ heap operations including

$k$ delete, deletemin and increasing changekey

operations, the total running time is $O(m + k\log n)$.

The provided Javascript implementation extends the forest data structure and includes the following methods.

The root of the first tree in the tree group defining a heap is used as the heap identifier. This is also a node with the smallest key. Two heaps can be melded simply by combining their groups. An insert is essentially just a meld of a singleton heap with another heap.

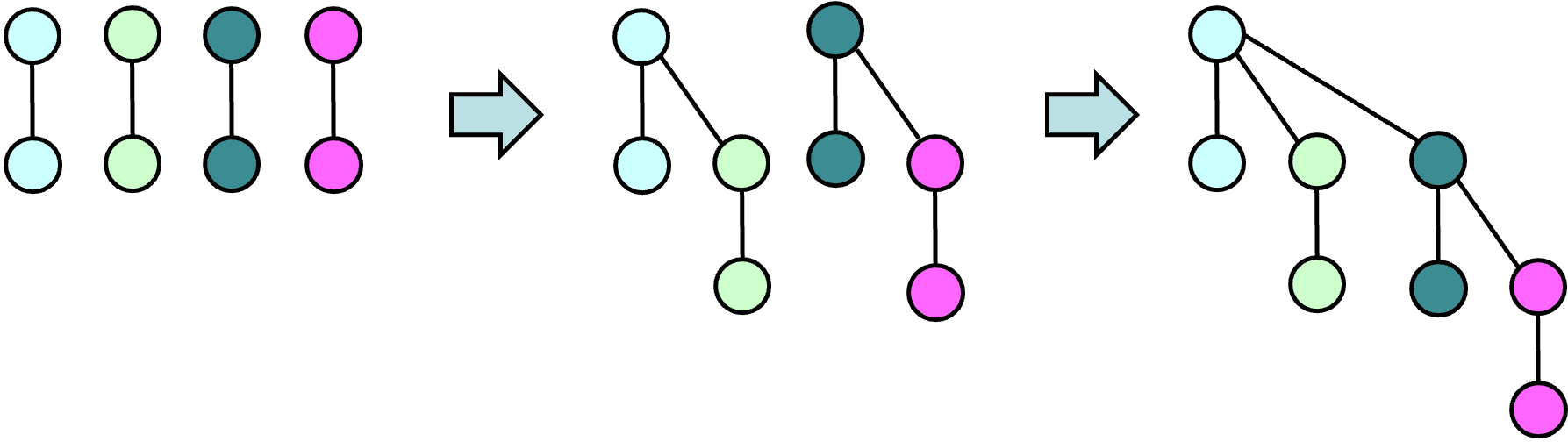

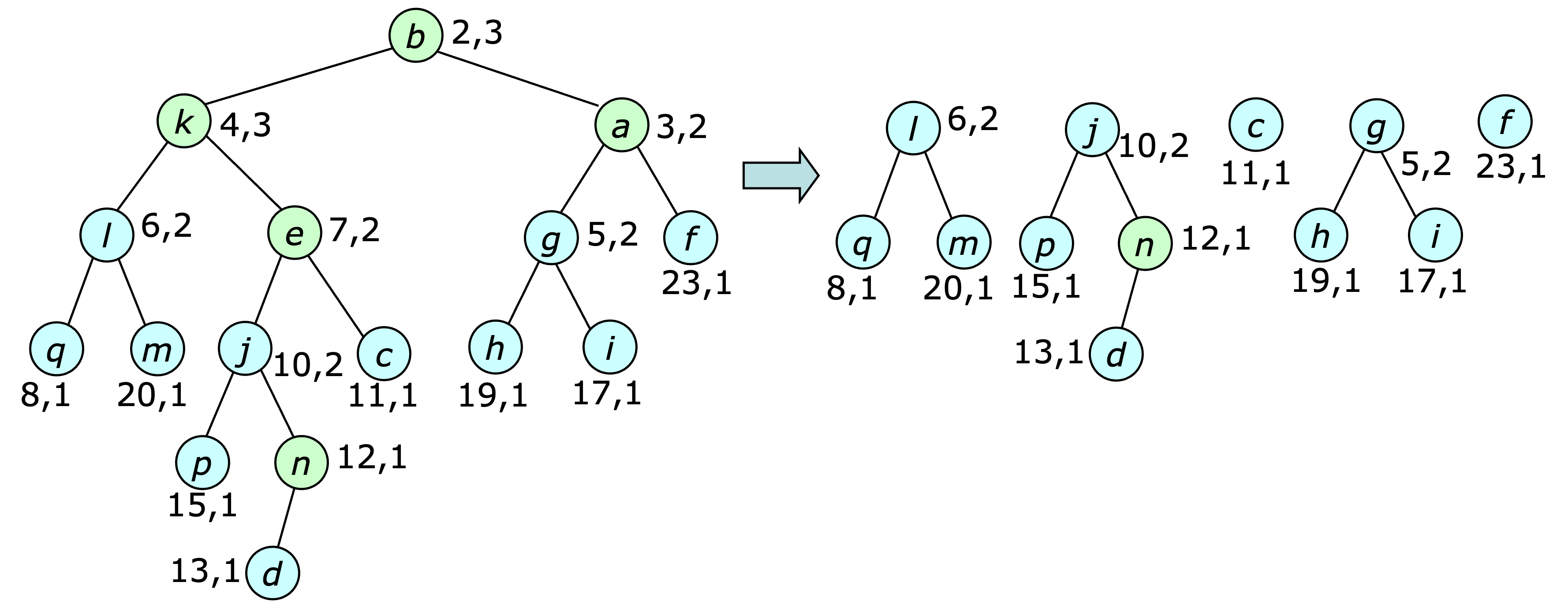

The $\deletemin$ operation for a heap identified by $h$ is implemented by removing each of $h$'s subtrees and adding them as additional trees in the heap; $h$ is then removed from the tree group. Next, the roots of the trees still in the heap are scanned to find the root with the smallest key. The heap is restructured at the same time to speed up later operations. In particular, trees with roots of equal rank are combined, with one tree becoming a subtree of the other's root. This is illustrated below.

This procedure can be implemented by inserting each tree root into an array at the position determined by its rank. Whenever such an insertion would collide with a previously inserted root, the two trees are combined with one becoming the subtree of the other tree's root (based on key value). The root that was previously in the array is removed and the root of the new tree is inserted at the position determined by its new rank. If this leads to a new collision, the process is repeated.

This restructuring process reduces the number of trees, speeding up subsequent $\deletemin$ operations. It also leads to a useful property, that can be observed in the example above. Note that after the process completes, the root node has a rank of 3, while its children have ranks of 2, 1 and 0, respectively. Also observe, that every node in the tree with a rank of $k$ has $2^k$ nodes in its subtree. This leads to an upper bound of $\lg n$ on the rank of any node.

Before discussing the $\changekey$ operation, let's analyze the performance of a sequence of $\insert$ and $\deletemin$ operations only. Let's start by showing that the property observed in the example is in fact a general property.

Lemma 1. Let $x$ be any node with rank $r$ and children $y_1,\ldots,y_r$, where the children are listed in the order that they became children of $x$. Then, $\rank(y_i) \geq i-1$.

Proof. First note, that if the only operations are $\insert$ and $\deletemin$, then only tree roots are ever removed from a heap. That means that no node in the heap ever loses a child. Also, a node can only become the child of another during the restructuring process performed by the $\deletemin$ operation. Consequently, just before $y_i$ became a child of $x$, $x$ had $i-1$ children. Since $y_i$ became a child of $x$ it must have collided with $x$ during the restructuring process and hence it must have had $i-1$ children, and since it hasn't lost any children it must still have $i-1$. $\Box$

Corallary 1. A node $x$ with rank $r$ has $2^r$ descendants in its subtree.

Proof. The proof is by induction on the rank, and clearly holds for $r=0$. For $r > 0$, the induction hypothesis and lemma imply that $x$ has $1 + 2^0+2^1+\cdots+2^{r-1} = 2^r$ descendants. $\Box$

This implies that the maximum rank is $\leq \lg n$, and that can be used to show that the initialization of the data structure followed by any sequence $m$ operations including $d$ $\deletemin$ operations takes $O(n + m + d\log n)$ time. This is done using a form of amortized analysis in which a set fictitious credits are allocated for each operation and used to “pay” for computational steps. Credits that are not needed to pay for a particular operation can be saved and used to pay for later operations. To ensure that there are always enough credits available, the algorithm adopts the following credit policy

Maintain one credit on-hand for every tree in all the heaps.

Note that the initialization of the data structure takes $O(n)$ time and leaves us with exactly $n$ trees. So, if $2n$ credits are allocated for the initialization, $n$ can be used to pay for the computation, leaving us with $n$ credits that can be used to satisfy the credit policy. Since an $\insert$ operation takes constant time and does not change the number of trees, a single credit can be allocated for each $\insert$ and used to pay for the operation.

For the $\deletemin$ operation the time required is bounded by the number of trees at the start of the restructuring process. If the deleted node has rank $r$, then the first step increases the number of trees by $r$, while the restructuring process may decrease the number of trees. If $p$ is the number of restructuring steps that involve a collision and $q$ is number that do not, then the total number of steps is $p+q$ and the number of trees at the completion of the process is $r-p$ larger than at the start. So, to pay for the operation and ensure that the credit policy is satisfied, $(p+q)+(r-p)=q+r$ credits must be allocated to the $\deletemin$ operation. To account for the case where $q$ and $r$ are both zero, one extra credit is allocated, and since both $q$ and $r$ are bounded by the maximum rank, $1+ 2\lg n$ credits are enough to pay for the operation and maintain the credit invariant.

This implies that the total number of credits allocated for the initialization plus $m$ operations including $d$ $\deletemin$ operations is $O(n+m+d\log n)$. Since every computational step was paid for from allocated credits, the running time is also $O(n+m+d\log n)$.

Now, it's time to consider the $\changekey(i,h,k)$ operation. When decreasing the key value, it can be implemented by first changing the key value, removing the subtree at $i$ and making it another tree in the heap's tree group. This is a perfectly fine way of implementing $\changekey$ but has the unfortunate side effect of breaking the analysis just completed. In particular, the key lemma requires that no node ever loses a child.

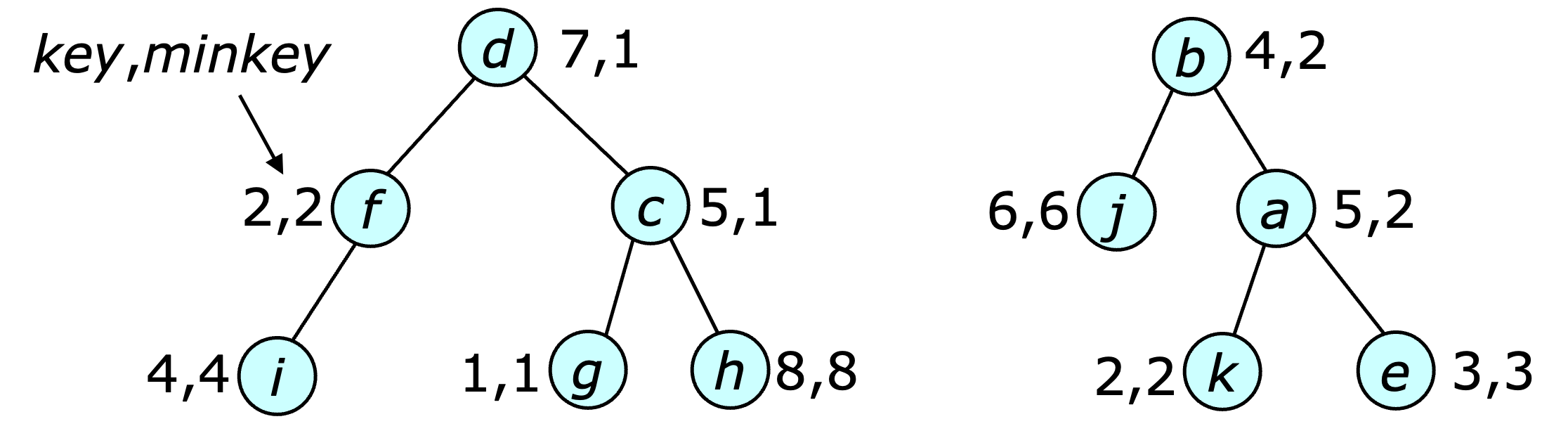

Fortunately, an alternate version of the lemma can be applied if the operation is modified to ensure that no non-root node loses more than one child. The new version sets the mark bit of a node $x$ whenever $x$ loses one of its children. If $x$ is already marked when $x$ loses a child, the subtree at $x$ is also removed and added to the heap's tree group (assuming $x$ is not already a tree root). If $x$'s parent is already marked, its subtree is also removed and added to the heap's tree group. This procedure is repeated until the parent of the subtree being removed is unmarked or is a root. The mark bits of all the new tree roots are cleared. This process is illustrated below.

Here is the new version of the lemma.

Lemma 2. Let $x$ be any node with rank $r$ and children $y_1,\ldots,y_r$, where the children are listed in the order that they became children of $x$. Then, $\rank(y_i) \geq i-2$.

Proof. As before, note that a node becomes the child of another during the restructuring process performed by the $\deletemin$ operation. Consequently, just before $y_i$ became a child of $x$, $x$ had at least $i-1$ children. Since $y_i$ became a child of $x$ it must have collided with $x$ during the restructuring process and hence it must have had at least $i-1$ children, and since it has lost no more than one child since it became a child of $x$, it must still have at least $i-2$. $\Box$

Corallary 2. A node $x$ with rank $r$ has at least $F_r$ descendants in its subtree, where $F_r$ is the $r$-th Fibonacci number.

Proof. The proof is by induction on the rank, and clearly holds for $r=0$ and $r=1$. For $r > 1$, the induction hypothesis and lemma imply that $x$ has at least $1 + F_0 + F_1 + \cdots + F_{r-2}$ descendants. This sum is equal to $F_r$. $\Box$

The Fibonacci numbers satisfy the inequality $F_r \geq \phi ^{r-2}$ where $\phi = (1 + \sqrt{5})/2$. Consequently, the maximum rank is $\leq 2 + \log_\phi n$.

To complete the analysis, the amortized complexity argument must be extended to handle the decreasing $\changekey$ operation. Here is a modified version of the credit policy.

Maintain one credit on-hand for every tree in all the heaps plus two credits for every marked non-root node.

As before, if $2n$ credits are allocated for the initialization, $n$ can be used to pay for the computation, and the remainder is enough to satisfy the credit policy.

Since an $\insert$ or $\meld$ operation takes constant time and does not change the number of trees or the number of marked nodes, a single credit can be allocated for each $\insert$ or $\meld$ and used to pay for the operation.

Since the $\deletemin$ operation makes no change to the number of marked nodes, the previous argument can be applied directly. The only change required is that the number of credits allocated to the step must increased to $1 + 2(2+\log_\phi n)$.

To determine the number of credits needed for a decreasing $\changekey$ operation, let $k$ be the number of new subtrees created by the operation. Observe that the number of marked non-root nodes decreases by $k-1$, while the number of trees increases by $k$. Consequently, $k-2$ fewer credits are needed to satify the credit policy following the operation. These $k-2$ credits plus 2 more are sufficient to pay for the computational steps.

All that remains is to analyze the $\delete$ and the increasing $\changekey$. These can both be implemented in terms of the other operations. Specifically, the $\delete$ operation can be implemented by doing a decreasing $\changekey$ followed by a $\deletemin$. The increasing $\changekey$ can be implemented as a $\delete$ followed by an $\insert$. Consequently the total number of credits allocated for the initialization plus $m$ heap operations that include $d$ $\delete$, $\deletemin$ and increasing $\changekey$ operations is $O(n+ m + d\log n)$. Since every computational step is paid for with allocated credits, the running time is also $O(n+m+d\log n)$. If $m\geq n$ (as it usually is), the bound can expressed more simply as $O(m+d\log n)$.

The core methods of the $\FibHeaps$ class are shown below.

To demonstrate in the web app, start with

let fh = new FibHeaps();

fh.fromString('{[a:2 b:4 c:1 d:3 e:4] [f:1 g:5 h:3 i:2 j:5]' +

'[k:1 l:5 m:3 n:2 o:4]}');

fh.deletemin(3);

log(fh.toString(0x1e));

The $\fromString$ operation creates three heaps with five

single node trees in each. A key is specified for each node.

The $\deletemin$ operation removes item $c$, from the first heap

and restructures it as shown below.

{a:2:2(b:4 d:3:1(e:4)) c:1 [f:1 g:5 h:3 i:2 j:5]

[k:1 l:5 m:3 n:2 o:4]}

The format argument for the $\toString$ operation causes the structure

of each tree to be shown explicitly, along with the key and rank of each node

(ranks of zero are omitted).

Note that brackets are omitted for heaps with a single tree

and that a deleted node becomes a single node heap.

Melding the three heaps and performing another $\deletemin$ yields

{c:1 f:1 [k:1:2(l:5 n:2:1(m:3)) o:4

a:2:3(b:4 d:3:1(e:4) i:2:2(j:5 h:3:1(g:5)))]}

The large heap has three trees, with roots $k$, $o$ and $a$,

with ranks 2, 0 and 3.

The operation $\changekey(8,11,1)$ produces this.

{c:1 f:1 [k:1:2(l:5 n:2:1(m:3)) o:4

a:2:3(b:4 d:3:1(e:4) i:2:1!(j:5)) h:1:1(g:5)]}

This prunes the subtree at $h$, making it the fourth tree in the

large heap. It also adds a mark to node $i$ ($h$'s former parent),

which is indicated by an exclamation point.

The Javascript implementation includes the following methods.

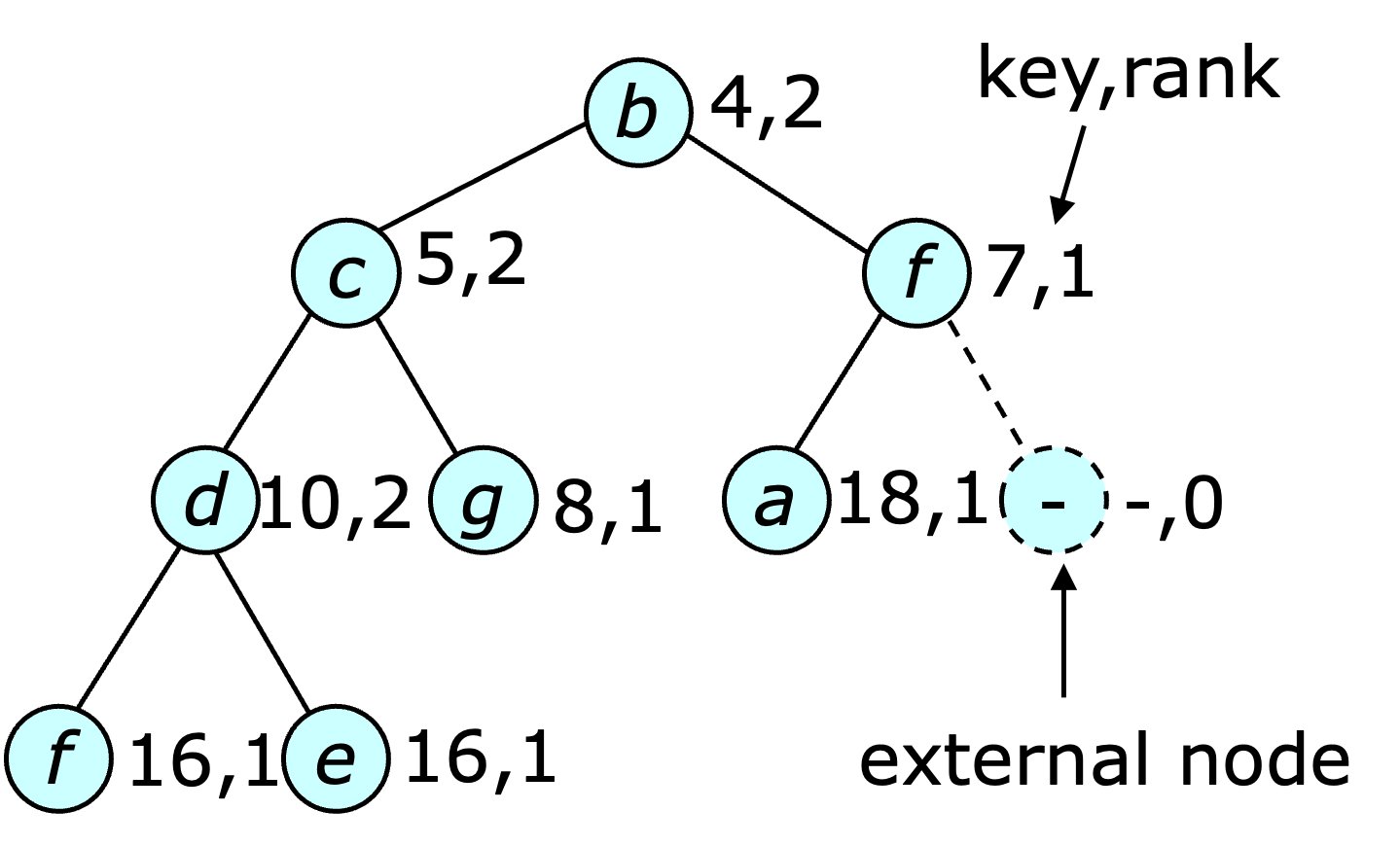

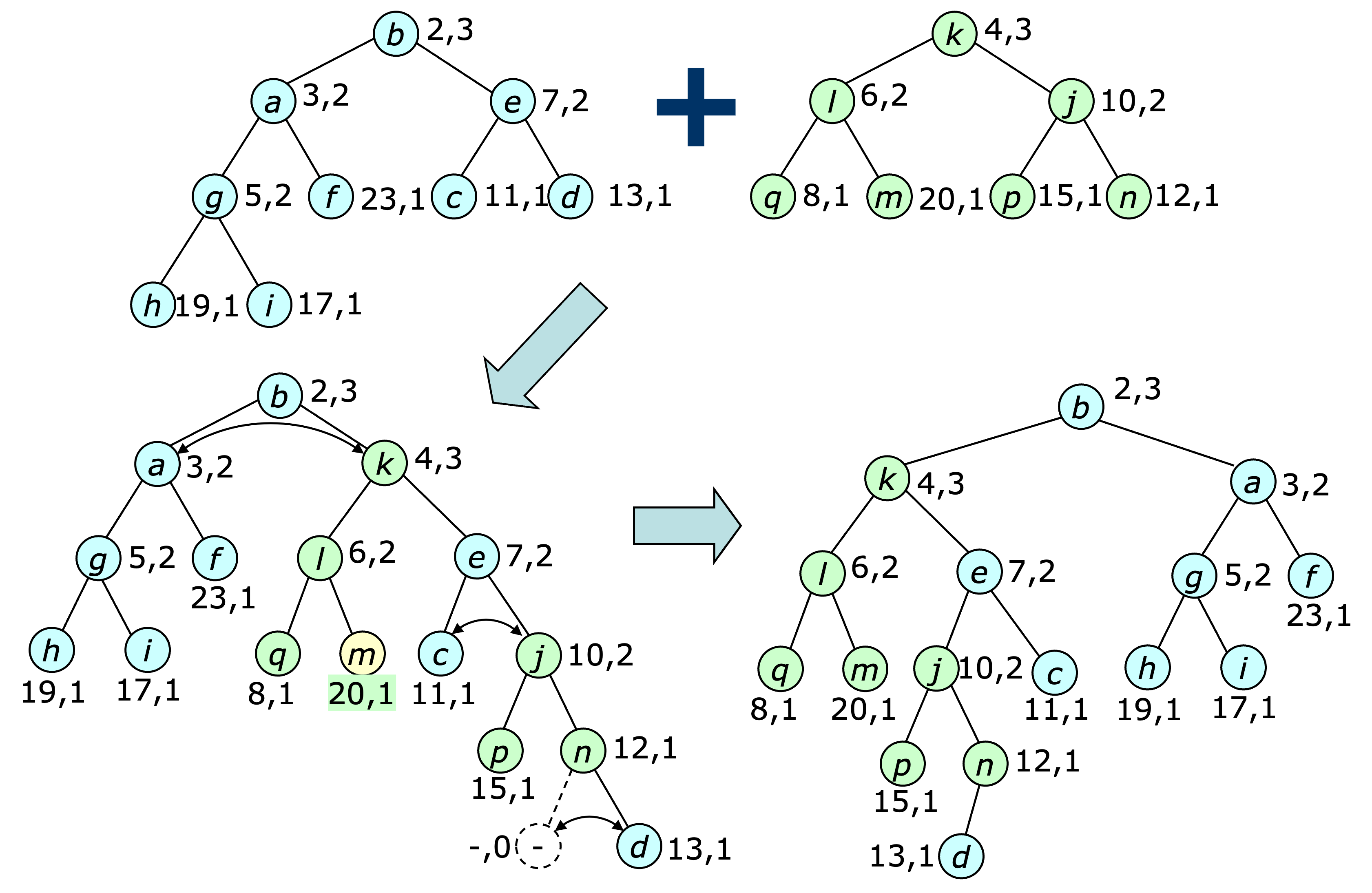

The $\meld$ operation is implemented by merging the right-most paths of the two heaps, based on the key values, then updating the ranks along the merge path, swapping left and right children as needed to ensure that the larger rank value is always to the left. This is illustrated below.

The $\insert$ operation is implemented by treating the item to be inserted as a single node heap and melding it with the heap it is to be inserted into. The $\deletemin$ operation is implemented by removing the root node and melding its two subtrees. The $\heapify$ operation is implemented by repeatedly removing the first two heaps from the list, melding them then appending the resulting heap at the end of the list. It terminates when there is a single heap on the list. Since the length of the right path from any node to the null node is at most $\lg n$, the $\meld$, $\insert$ and $\deletemin$ operations all take $O(\log n)$ time. The analysis of $\heapify$ is a bit more complicated. The first step is to divide the processing into passes, where a pass ends when all the heaps on the list at the start of the pass have been removed and melded with some other heap. If there are $k$ heaps on the list intially, the number of passes is at most $\lg k$, since each pass reduces the number of heaps by a factor of 2. If there are $r$ heaps on the list at the end of a pass and the heap sizes are $n_1, n_2,\ldots, n_r$, then the time for the pass is $$ O \left(\log n_1 + \cdots + \log n_r \right) = O \left( r \log n/r \right) $$ since the value of the sum is maximized when all heaps are the same size. Consequently, the total time for $\heapify$ is $$ \begin{eqnarray*} O\left( \sum_{j=1}^{\lfloor \lg k \rfloor} (k/2^j) \log ( 2^j n/k) \right) &=& O\left( k \sum_{j=1}^{\lfloor \lg k \rfloor} (j/2^j) + (1/2^j) \log ( n/k) \right) \\ &=& O\left( k\max(1, \log(n/k)) \right) \end{eqnarray*} $$ The core methods of the Javascript implementation are shown below.

To demonstrate leftist heaps in the web app, start with

let lh = new LeftistHeaps();

lh.fromString('{[a:2 b:4 c:1 d:3 e:4] [f:1 g:5 h:3 i:2 j:5]' +

'[k:1 l:5 m:3 n:2 o:4]}');

fh.deletemin(3);

log(fh.toString(0x1e));

The $\fromString$ operation creates three heaps

with a key specified for each node.

The $\deletemin$ operation removes item $c$, from the first heap

and restructures it yielding this.

{[b:4 *a:2:2 (e:4 d:3 -)] c:1 [(h:3 i:2:2 j:5) *f:1:2 g:5]

[(m:3 n:2:2 o:4) *k:1:2 l:5]}

The format argument for the $\toString$ operation causes the structure

of each tree to be shown explicitly, along with the key and rank of each node

(ranks of 1 are omitted).

Note that in this case brackets are included for all but singleton heaps.

Melding the three heaps and performing another $\deletemin$ yields

{c:1 f:1 [((e:4 d:3:2 g:5) a:2:3 ((l:5 b:4:2 j:5) i:2:2 h:3))

*k:1:3 (m:3 n:2:2 o:4)]}

The presence of retired or dummy nodes means that the “true” minimum key node may not be at the root of a heap's tree. Consequently, the $\findmin$ and $\deletemin$ operations must start with an initial step that traverses the top of the heap, removing all the retired/dummy nodes that it finds and constructing a list of sub-heaps for which the roots are not retired or dummy. This is illustrated below, with retired/dummy nodes shown in green.

Heap items can also be retired implicitly, using a client-provided retired function. If such a function is provided, it is used to determine if a node should be considered retired, instead of consulting a stored bit. This eliminates the time spent marking nodes as retired and is particularly useful if a single step in an application may make many heap nodes no longer relevant at the same time. Rather than force the application to identify and mark each of these nodes, it can be more efficient to identify them with a function call when it's time to purge them from the heap-ordered tree.

The core methods of the $\LazyHeaps$ class are shown below.

To demonstrate lazy heaps in the web app, start with

let lazy = new LazyHeaps();

lazy.fromString('{[a:2 b:4 c:1 d:3] [e:4 f:1 g:5 h:3] ' +

'[i:2 j:5 k:1 l:5 m:3]}');

log(lazy.toString(6));

lazy.retire(8);

let h = lazy.lazyMeld (3,6); h = lazy.lazyMeld(h,11);

log(lazy.toString(6));

The $\fromString$ operation creates three heaps and the two lazy meld

operations combine them into the single heap as shown below.

{[(b:4 a:2 -) *c:1 d:3] [e:4 *f:1 (g:5 h:3 -)]

[(j:5 i:2 -) *k:1 (l:5 m:3 -)]}

{[(((b:4 a:2 -) c:1 d:3) D (e:4 f:1 (g:5 R -)))

*D ((j:5 i:2 -) k:1 (l:5 m:3 -))]}

The tree structure is shown explicitly.

Note that each of the dummy nodes added by lazy melds are shown as

a capital “D&rdquo, while the retired node is shown as

a capital “R“.

A $\findmin$ operation eliminates the two dummy nodes from the top of the tree, and combines the resulting three subtrees giving

{[(((g:5 R d:3) f:1 e:4) c:1 (b:4 a:2 (l:5 m:3 -)))

*k:1 (j:5 i:2 -)]}

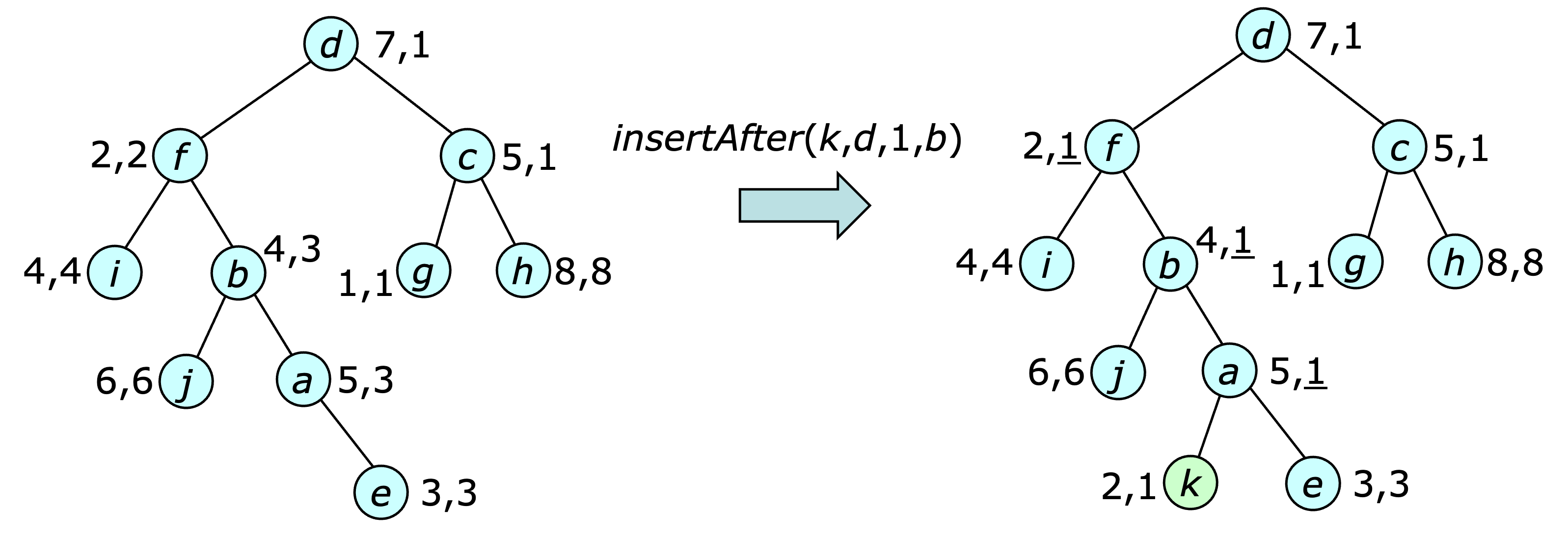

The $\addtokeys$ method is implemented by adding the specified increment to a per-heap offset value. When an item is inserted into a heap, the saved key value is adjusted to reflect the offset, so that at all times the sum of the stored key value and the offset is equal to the user-specified key. The saved $\minkey$ values also reflect the offset, so the minimum key in the subtree of an item is equal to the sum of the stored value and the offset.

The $\divide$ method is implemented using the $\split$ method of the underlying balanced binary forest data structure. Note that the split method uses $\join$ operations in its implementation, so the ordered heap method provides a $\join$ operation for this specific purpose. The provided $\join$ operation uses the $\refresh$ operation to maintain the validity of the $\minkey$ fields. The provided $\join$ operation does not work in general contexts, since it requires that the components being joined together all have the same offset.

The core of the Javascript implementation appears below.

To demonstrate the $\OrderedHeaps$ data structure, enter the following script in the web app.

let oh = new OrderedHeaps(10);

oh.fromString('{[b:2 a:1 d:4 c:3] [h:8 g:7 j:10 i:9 f:6] [e:5]}');

log(oh.toString(4), oh.x2s(oh.findmin(oh.find(10))));

oh.insertAfter(5,5.5,10,oh.find(10)); oh.add2keys(1,oh.find(1));

log(oh.toString(4));

This produces the output below.

{[b:2 *a:1 (- d:4 c:3)] [h:8 *g:7 (j:10 i:9 f:6)]} f

{[b:3 *a:2 (- d:5 c:4)] [h:8 *g:7 ((- j:10 e:5.5) i:9 f:6)]}